David LaFevor

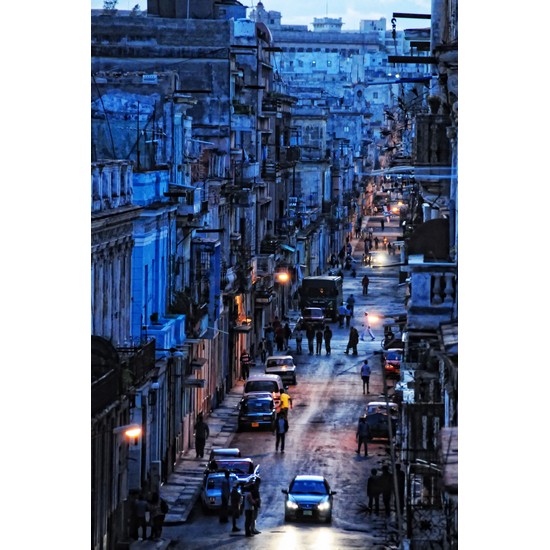

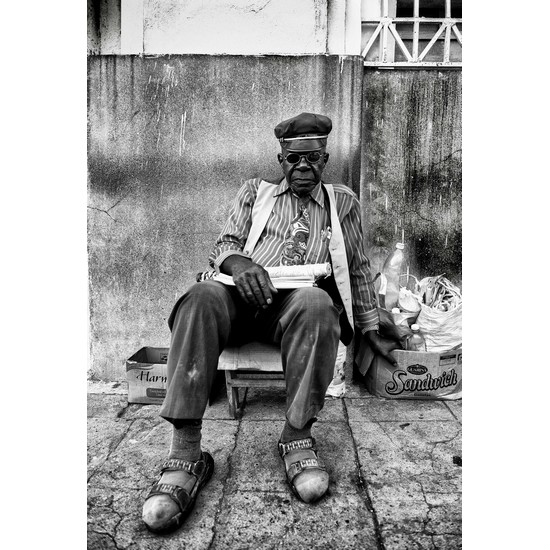

Part of my work as a professor of Latin American History and Digital Humanities centers around the discovery and preservation of previously unknown archival documents in untraveled corners of Latin America. Specifically, my preservation initiatives over the last twenty years have focused on the African Diaspora in Latin America, with years of living and working in Cuba, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Peru, and Argentina. My teams have preserved and digitized millions of documents that provide the only proof of life for tens of millions of enslaved and free Africans and Afro-Latin Americans from the fifteenth to late nineteenth centuries. My photographs during that period attempt to create visual narratives and histories of the present. Through portraiture, street photography, and photo documentary image making, I’ve sought to illuminate the interactions of the histories of enslavement, present contextual complexities, and the ability of Afro-Latin Americans to do what Cubans call resolver, to bend challenging objective conditions into desired outcomes. As an historian of slavery and the slave trade, my images in the present provide a visual record that I wish existed for the past. They do so, I hope, while preserving the dignity of my subjects within conditions of material poverty. My process is straightforward, but has been honed by years of experience outside of the archive. I walk the streets in the towns, villages, and cities where I work, making friends and collecting narratives. The camera emerges only after conversation and the establishment of trust and genuine interest, often massaged by sharing a few drinks and hours of discussion. Over the years, I’ve amassed a portfolio of thousands of images of Latin America and the American South. I print most of these myself, aside from large format metal prints. My photographic training was an apprenticeship under my father, who was a highly sought-after architectural and commercial photographer for fifty years. He taught me large and medium formats, mainly 8×10 and 4×5, and I’ve expanded this training into 35mm DSLR given that tools greater portability in the often remote regions where I work. It is my hope that my historical and photographic endeavors fuse the visual richness of Walker Evans with the humanistic and historical curiosity of the historian Marc Bloch, and that it also provides my students with a sense of the complexity of the interactions of past and present.